Formulating Infrequently Asked Questions

In early April, with the onset of a major shift in U.S. trade policy, global financial market volatility increased materially. The U.S. Treasury and currency markets saw unusual trading activity, which spilled into the stock market. In the ensuing days, a stream of reports and articles began questioning the credibility of the U.S. dollar (USD) and the safe-haven status of U.S. Treasury debt. A few clients reached out after reading predictions about an existential crisis for the USD. One asked, “We are not traveling to Europe this year. Do I need to worry about the dollar?”

Over the years, our clients have rarely raised questions about the USD. Even so, discussions within our investment team frequently center on the prospects for the dollar and how to protect client purchasing power if the USD were to weaken significantly. We expect that the USD will become a more central point of conversation in future client meetings.

So far, the evidence suggests that the unusual trading activity of early April, including the spike in interest rates and a lower USD price, was at least partially caused by the unwinding of large speculative currency bets placed with leverage. Since then, long-term interest rates have fallen, and the dollar has recovered somewhat against most currencies.

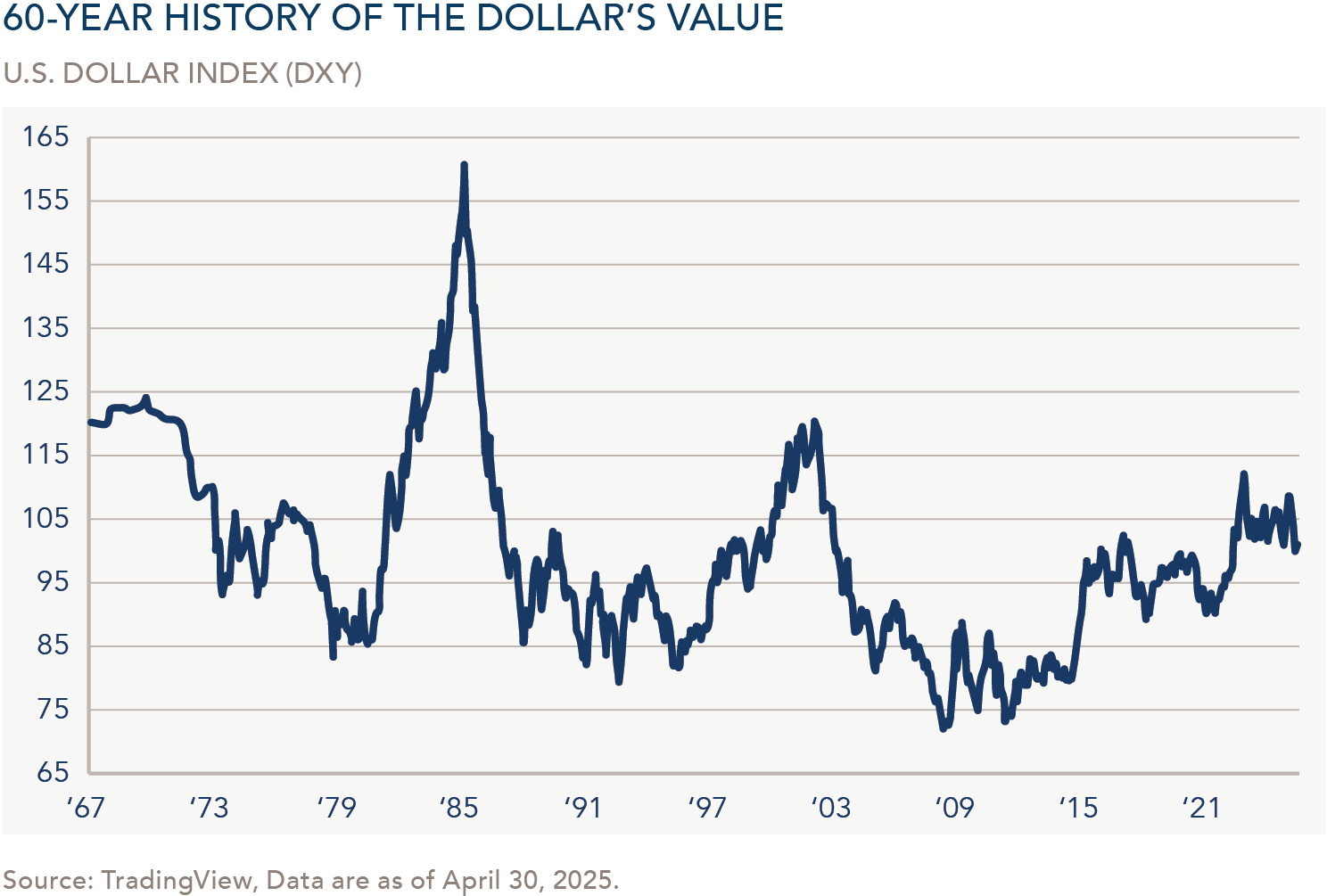

To frame the USD’s recent moves, it’s worth noting that market participants often look to the DXY Index, which represents the value of the USD relative to a weighted basket of six foreign currencies. Interestingly, the DXY does not include the currency of our significant trading partner, China. As the chart below illustrates, the U.S. dollar has shown no decisive long-term trend over nearly 60 years. Since the Great Financial Crisis (2008–09), the dollar has generally appreciated. Based just on its trading history, the recent pullback looks like a correction.

So why all the noise?

One explanation comes from Swiss investment manager Felix Zulauf, who warned post-Covid that currency volatility would increase meaningfully—and that a few major currencies could even fail. Zulauf observed that as central banks increasingly intervene in their own bond markets, the cost of capital (yields) is being distorted. Historically, sovereign stress showed up through bond yields; today, it increasingly shows up in currency prices. His broader point: in an era of financial repression, currency markets may now be the best signal of stress and future dislocation. If so, the USD’s recent softness, even if not extreme, has drawn outsized attention for good reason.

A second, broader concern is that the stable currency regime of the last 75 years may be nearing a breaking point. Under this regime, the USD has served as the undisputed global reserve currency. But massive global demand for USD assets—while reflecting trust—has also introduced real distortions. These include persistent U.S. trade deficits, elevated foreign ownership of U.S. assets, and a feedback loop in which global savings chase USD exposure because of its dominance in trade, commodities, and financial markets.

To illustrate: over 50% of all global trade is executed in USD; 90% of foreign exchange (FX) trades have the USD on one side; and U.S. equities represent 65% of total global market cap. These statistics underscore the dollar’s centrality, but also raise questions about sustainability, especially given that the U.S. economy makes up only ~4% of the global population and 25% of GDP.

The Trump Administration has begun questioning the costs of this dollar-centric system. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent argues that the “exorbitant privilege” of reserve currency status has created competitive disadvantages for the U.S., including an overvalued dollar and hollowed-out manufacturing base. The administration’s proposed remedies (new tariffs and strategic decoupling) suggest that a deliberate rebalancing is underway. A weaker dollar, over the short to medium term, may serve that agenda.

Many observers worry that this shift may trigger inflation, dampen global growth, or even spark a loss of confidence in U.S. assets. While we see these as valid risks, they could be construed as part of a difficult but potentially constructive realignment rather than the early stages of a currency crisis.

International actors are watching closely. The BRICS+ nations (including the original five: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) have been especially vocal in challenging USD dominance, and there are rumors of a new quasi-fiat currency—potentially backed by commodities like gold. Central banks in China and Russia have resumed gold accumulation, which may support such ambitions. While we are skeptical of a near-term rival emerging to the USD, these efforts reflect global interest in alternatives.

Relatedly, gold has reached new highs in USD terms, rising over $1,000 per ounce in the past year. Some interpret this as desperation for safe-haven assets. We see it more as a rational hedge against financial imbalances, just as increased interest in cryptocurrencies likely reflects similar instincts.

Looking ahead, more turbulence is possible as U.S. policymakers attempt to renegotiate terms of global trade and capital flows. That turbulence may include periods of USD weakness—but that does not necessarily imply crisis. Indeed, there have been extended periods of dollar depreciation in the past, and those environments often created attractive entry points for investors: valuations abroad tend to improve, U.S. exports become more competitive, and capital allocators can benefit from diversification.

“Even if the dollar weakens modestly, those foundational strengths endure.”

Ultimately, we believe the U.S. economy remains well-positioned, with a broad and innovative corporate base, deep capital markets, and a rule-of-law system that remains the envy of the world. Even if the dollar weakens modestly, those foundational strengths endure. Yes, the U.S. remains exceptional!

So what are the right questions for investors to ask? In our view, they include:

How might global capital flows shift if the USD becomes less dominant over time?

This is a tough one. Over time, we could see alternative safe-haven assets emerge to attract stable capital. What we do know is that current global imbalances appear significant. When capital moves away from popular USD-denominated assets, inflows into smaller or overlooked asset classes could generate solid returns.

Which asset classes (or geographies) stand to benefit in a weaker dollar environment?

In previous periods of USD devaluation (1968-1981 and 2000-2011), capital tended to flow from large to small companies, from financial assets to real assets, and from U.S. stocks to international equities. We expect history to repeat, or at least rhyme, again this time.

How can we build portfolios that are resilient to regime change in global finance, yet nimble enough to seize opportunity?

We favor maintaining high levels of liquidity through short-maturity, high-quality fixed income assets, such as U.S. Treasuries. If shifts in USD flows drive up the cost of capital in the U.S., we anticipate extending portfolio durations (maturities) and increasing exposure to credit risk. We also expect to reallocate (tax efficiently) away from popular, overvalued USD equities toward international markets and less crowded, undervalued areas of the U.S. stock market.

These aren’t frequently asked questions, but they may be the most important ones for long-term capital stewards.

The above information is for educational purposes and should not be considered a recommendation or investment advice. Investing in securities can result in loss of capital. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance.