U.S. Exceptionalism and What It Means for Your Portfolio

Over modern U.S. history, we’ve hardly gone a moment without hearing predictions of America’s imminent downfall. In that sense, you might say that declinism is one of the great American past times.

During his 1960 Presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy painted a scary picture of a Russian enemy well on its way to world domination as the U.S. risked entering a “long, slow afternoon”. That gave way to the 1970s when the crumbling U.S. dollar, generational revolt, and setbacks in world affairs stoked new predictions of America’s collapse. Then came the 1980s when the world became enraptured with Japan—a country where government and business worked hand in glove and where moral depravities like crime seemed to hardly exist. How could the U.S. hope to compete with Japan’s cars, computers, and single-minded commitment to greatness?

Yet the reality is that the United States has pulled ahead of the rest of the industrialized world. You’d in fact be hard-pressed to think of a point in history when the U.S. economy has diverged so dramatically from its peers. Today, American economic output per person is 40 percent higher than in Western Europe and 60 percent higher than in Japan, much bigger gaps than at the start of the 1990s.

The Forces Behind U.S. Exceptionalism

Far more than just a run of luck, our country’s prosperity has been based on structural advantages that are enduring. A simple but overlooked one is our geography. While the internet has made the world feel smaller, borders still matter. We benefit from a remarkable margin of security from having friendly neighbors to the north and south (tariff threats notwithstanding). Meanwhile, America is flanked by two vast oceans, putting us a great distance from continents with long histories of conflict. While the U.S.’s strengths are varied, we should not take for granted that where we sit on the world map has afforded us the time and space to strengthen our institutions relatively free from outside threats.

“Far more than just a run of luck, our country’s prosperity has been based on structural advantages that are enduring.”

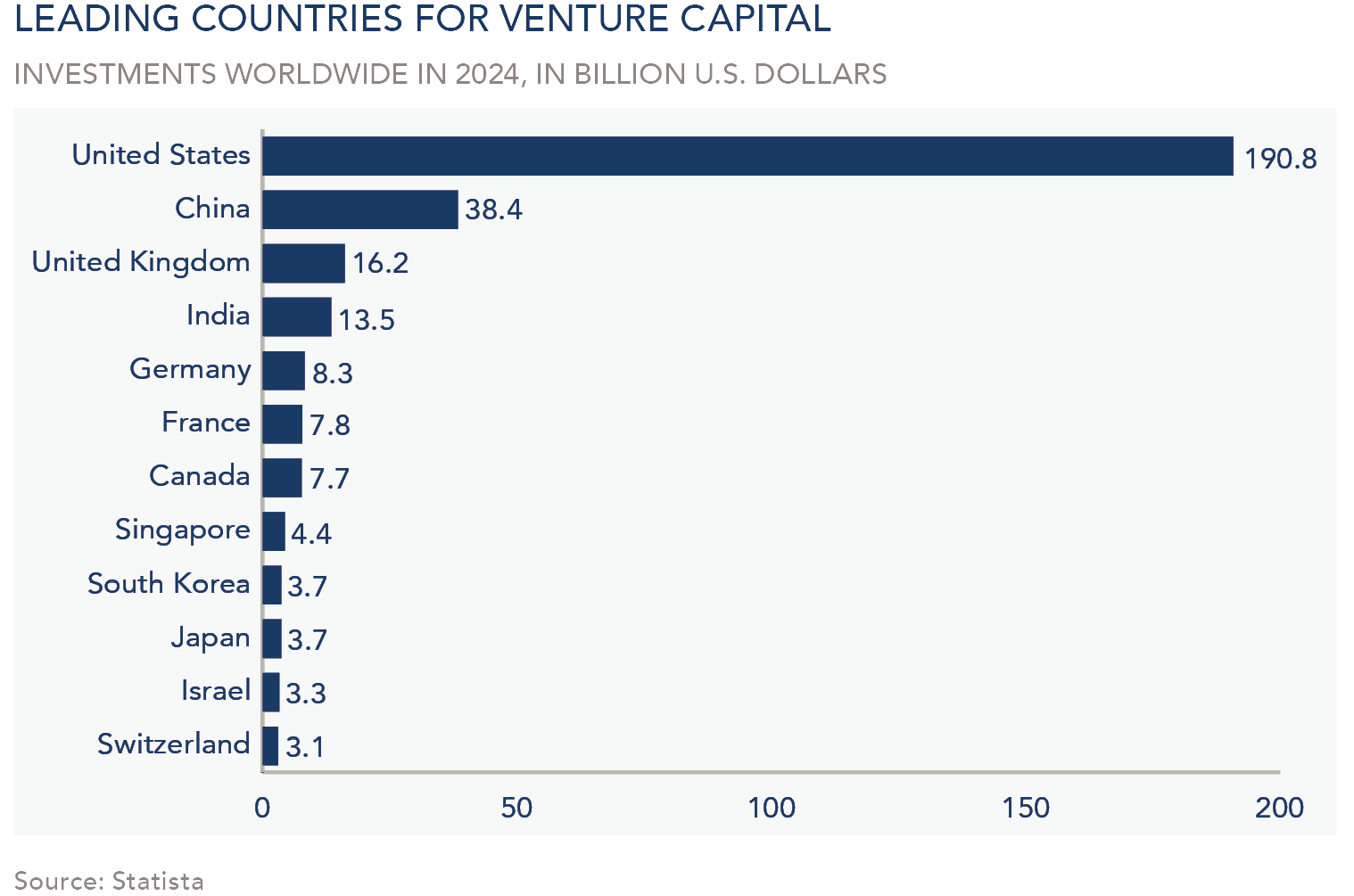

Another advantage is America’s culture of innovation. Despite long enjoying the lead position among industrial nations, Americans do not rest on their laurels. The U.S. accounts for the lion’s share of the world’s venture investing as well as R&D spending, building upon an already imposing foundation of institutional knowledge. Important, too, is that we do not shy away from reinvention. American companies and jobs generally churn at higher rates than they do in the rest of the world. With new beginnings comes a redeployment of capital towards more productive uses. This has been a boon to our country given the technological leaps that have taken place in the last two centuries, enabling our successful journey from an agrarian to an industrial to a knowledge-led economy.

America’s economic leadership is also underpinned by the strong support we give to businesses. Ideas go to market with relative ease. With 50 states competing for their capital, businesses can situate themselves according to their needs around labor, natural resources, transportation infrastructure, and their target customers. Once established, a company that hatches a great idea can bring it to the rest of the country in short order as the U.S. effectively operates as a single market, helped further by having access to the deepest capital markets in the world. While it’s fair to lament how dominant the largest corporations have become, especially in the public arena (witness how concentrated the S&P 500 Index is at the top), bear in mind that they are often the training grounds for the next crop of founders. As a testament to the dynamism of the U.S. economy, the roster of leading companies tends to change significantly from decade to decade.

“With new beginnings comes a redeployment of capital towards more productive uses.”

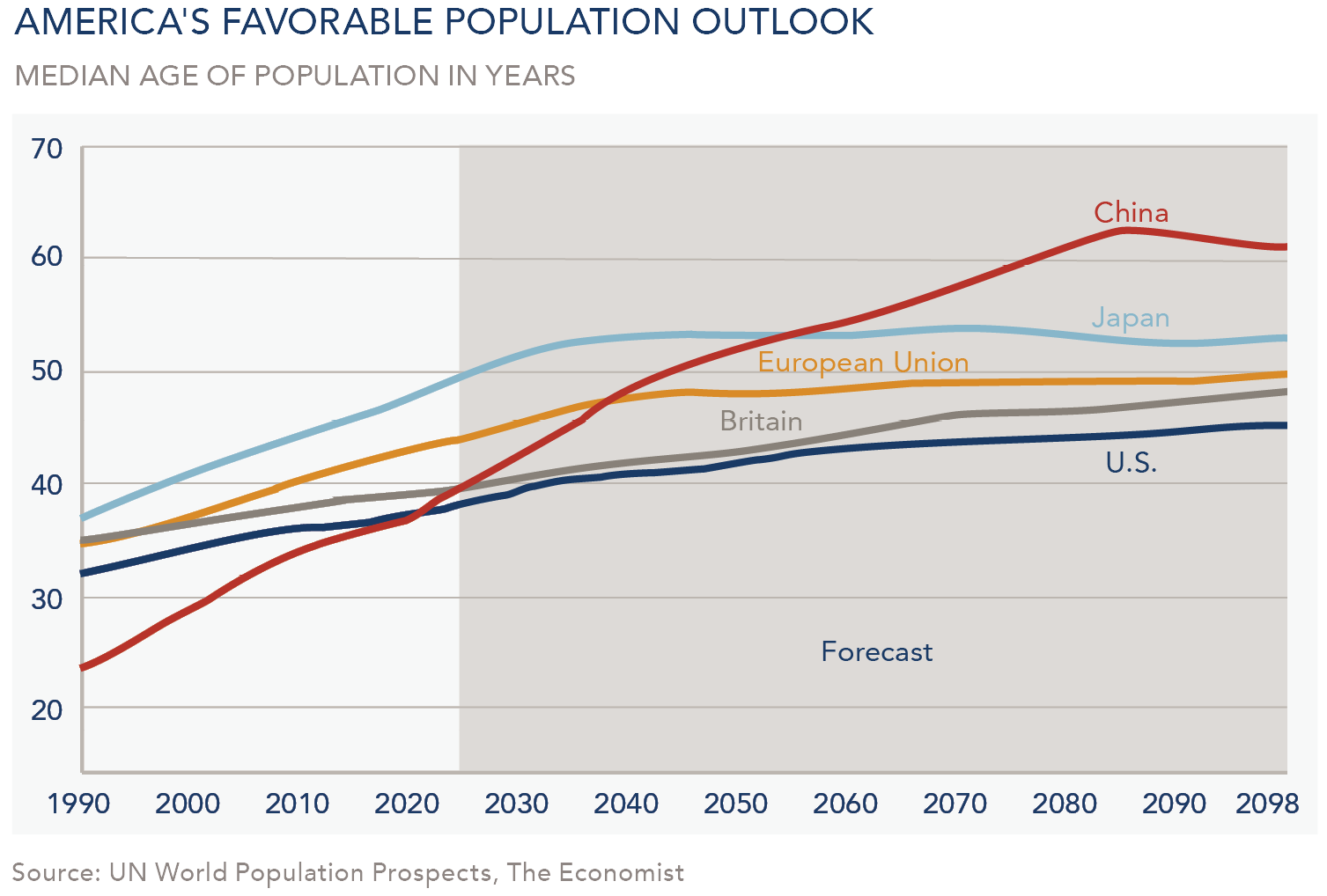

Demographics will be important to maintaining U.S. leadership. As countries age, they must contend with a shrinking labor pool and a downshift from investing in growth to spending on basic services. Though Americans are having fewer children, so is the rest of industrialized society. We’re expected to at least maintain our share of the world’s population at 4 percent through 2100. Meanwhile, China’s share is expected to fall from 18 to 6 percent, and the European Union’s from 6 to 3.5 percent. Under such a scenario, America’s relative standing isn’t assured. But it would surely be harder to prosper without a baseline of human capital.

Could U.S. Exceptionalism End?

History suggests that it’s only a matter of time before we cede ground to the next superpower. The great nations that came before us followed unique paths but their declines were typically precipitated by rising public debts that became crippling. That’s worrying as the U.S. is currently spending far more than we collect in tax revenues with the fiscal deficit projected to widen in the coming years. One mode of thinking is that deficits don’t matter so long as the U.S. dollar remains in demand and the world is willing to fund our debt obligations. But the passing of the torch to the next great economic miracle—or our transformation into a more multi-polar world—could mark a turning point in the desirability of dollar-based assets.

Looking around the globe, China is a natural candidate to one day overtake the U.S. on its sheer size alone. As a centrally planned economy, its leadership can create outcomes through brute force. But even if China’s annual economic production eventually surpasses ours, that alone does not confer superpower status. Looking to an abstract measure called inclusive wealth (referring to a nation’s entire stock of intangible and physical capital whereas GDP only represents a snapshot of economic output), the United Nations’s analysis suggests that the U.S. could remain leagues ahead of the pack. Further, there are questions on whether tomorrow’s emerging powers would be able to truly project their size into meaningful leadership across cultural, political, and military domains, which is no easy feat.

“Given our economy’s inherent strengths, there’s reason to be optimistic about the future and to favor home-grown assets.”

That brings us to the state of U.S. democracy. We are operating in an era of extremely fractured politics. If America enters a period of isolationism, we risk driving allies and trade partners away from the U.S.-centric financial system. That should be a frightening thought for investors. But we should remind ourselves, too, that democracy is not always satisfying to watch and that political rancor at least signals our willingness to take a magnifying glass to the things that need our attention. America’s tradition around public discourse has itself been a force for self-preservation, including when we’ve faced existential threats like the 2008 banking crisis and the Covid pandemic.

“…the world is sure to change for generations to come in ways we cannot possibly predict today.”

What does this all mean for U.S. investors? Given our economy’s inherent strengths, there’s reason to be optimistic about the future and to favor home-grown assets. Still, we continue to recommend that clients diversify their portfolios abroad in acknowledgment of the unpredictable nature of market cycles and out of our team’s success in identifying attractive foreign investments. Diversification into non-U.S. assets should also make sense to any student of history: past superpowers looked unstoppable until they eventually weren’t, and the world is sure to change for generations to come in ways we cannot possibly predict today.

The above information is for educational purposes and should not be considered a recommendation or investment advice. Investing in securities can result in loss of capital. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance.